Most people that have used Reason since version 1.0 might already be very familiar with the Subtractor. It was the first synth in Reason, and at the time, was the only synth in Reason. However, if you are just coming into Reason right now (version 6.5), you may not have ever used the Subtractor. Or maybe you haven’t touched it in a very long time. So this article will present some of the basic building blocks of Subtractor sounds. Use these 25 patches as starting points for your own creations, or use them as is. What I tried to do here is show some of the capabilities of the Subtractor synth via example patches. There’s no CV, no Combinators. Just straight single Subtractor sounds. As well as some tips for working with this — still amazing — synth.

Most people that have used Reason since version 1.0 might already be very familiar with the Subtractor. It was the first synth in Reason, and at the time, was the only synth in Reason. However, if you are just coming into Reason right now (version 6.5), you may not have ever used the Subtractor. Or maybe you haven’t touched it in a very long time. So this article will present some of the basic building blocks of Subtractor sounds. Use these 25 patches as starting points for your own creations, or use them as is. What I tried to do here is show some of the capabilities of the Subtractor synth via example patches. There’s no CV, no Combinators. Just straight single Subtractor sounds. As well as some tips for working with this — still amazing — synth.

You can download the patch pack here: Basic-Subtractor. It contains 25 Subtractor patches that are used as examples to show how various basic sounds are generated with the device. Use these as they are, or use them as springboards for your own designs.

So try out the patches, and if you like them please consider donating: [paypal-donation]

The Subtractor is a very straightforward 2-Oscillator synth that is based on subtractive synthesis. It’s modelled to react in the same way an Analogue synthesizer would, even though it’s a digital recreation of one. Its subtractive synthesis engine means that the Oscillators make up the tones, and these tones can be shaped and whittled down between each other, and with mixing and filtering to remove or subtract parts of the sound for a final outcome. Creating sounds is like covering up an entire canvas with a coat of black , and then painting by removing those black areas to reveal the painting underneath. Or rather, painting using the negative space, as opposed to the positive space. This is the basic idea that forms the wealth of sounds you can gleen from the device.

The following shows the Subtractor device, with the “Init Patch” loaded. The Init Patch is used as a starting point for building sounds. Note that the Init Patch does not start at ground zero, and instead is an actual patch that generates an actual sound. I find that in some circumstances you may want to start at ground zero. In this case, you can set all the sliders and knobs to their zero or center position and save the patch. This way, you can always load your new “Init Patch” anytime you like. I’m sure only the die hard sound creation gurus will go to this trouble, but if you are new to any synth, it’s always better to learn from the bottom up, than to have half a sound already generated for you. But that’s just my own opinion.

The Patches

Following are the various patch examples you will find within the patch pack, along with a brief description and key features of each. The idea behind these patches are to show you the versatility of the synth, and show some of the types of sounds it can produce. Of course, there are many more kinds of sounds. An oboe, bassoon, an ambulance siren, and the list can go on. I encourage you to try your own. But hopefully these can get you started and give you some ideas of how to work with the Subtractor.

-

Bass Example

-

Bass Wobble Example

-

TB303 Example 01

-

TB303 Example 02

These patches are probably the type of sound that is most commonly associated with the Subtractor: Bass. Octave separation between the two oscillators is key here, along with the right kind of filtering and amp envelope.

-

ChipTune Example

This type of sound is one that you’d find on any video game console from the ’80’s. The key to this kind of sound is use of the LFO set to square wave and modifying Oscillator Pitch. This creates the arp feel of the patch. In addition, the Band Pass Filter and setting the envelopes to a full decay and all other envelope parameters to zero gives the sound a minimal 8-bit feel. If you wanted to, you could use the Noise generator to add a little distortion to the sound. But it’s usually better to add a Scream FX unit set to “Digital” damage mode in order to recreate some “crunch” to the sound. Be sure to also keep the Oscillator waves simple as well. Remember, you’re trying to recreate very basic technology here.

-

Filter Sweep Example

This shows you how the Filter Envelope can be used to sweep the filter in your sounds.

-

Flute Example

-

Horn Example

These two patches show you how you can create some wind instruments. One of the keys to recreating these types of sounds is using the sawtooth oscillator and proper filtering. A little modulation helps as well. Generally, I find wind instruments use either Sawtooth or Sine waves, and benefit from a HP filter in Filter 1 and a then the Low Pass filter 2. Some tweaking with the envelopes and a little modulation affecting the pitch to give it a jump in pitch at the beginning can recreate the “blowing” sound that starts at the beginning of these sounds. As with everything in patch design, the devil is in the details.

-

FM Texture Example

Shows how using FM can give a whole new perspective to your sound, and can often generate interesting textures. FM, as well as Ring Mod can make the sound very unnatural, distorted, or even metallic. See the next “Glockenspiel” patch.

-

Glockenspiel Example

This is an example of a glock — or bell-like sound. The use of the Ring Mod feature is what really makes the sound here. The example presented is tonal, because the Oscillators are set one octave apart. But you can get some really interesting atonal bell sounds by separating the Octave in weird degrees (for example, try separating them by 6 or 9 semitones, or play around with odd “Cent” differences).

-

Guitar Example

Guitars are difficult — probably the most difficult — to reproduce. But if you can reproduce a piano sound with a synth, you can take an extra leap to try a Guitar sound as well. The two actually share some similar concepts I think. And while the Subtactor isn’t perfect for guitars, they are still do-able. I found that using Wave 15 in Oscillator 1 paired with a sawtooth provided the raw tones. Then a Bandpass filter 1 going to the Low Pass filter 2 seemed to work out well. I then set the Filter and Amp envelopes to similar values, with medium Decay and Release on both. Keep the Attack at zero to give that initial hard attack. The sustain is tricky, and you can leave it out if you want, or add just a little bit to keep the sound going. That’s your call. The other key to this sound is adding a little FM for a metallic sound. Then turn the Mix knob all the way left so that you’re only hearing the FM Carrier (Oscillator 1). That’s the basis for a typical Subtractor Guitar sound. But play around to see what type of sounds you can build from this technique.

-

Hi Hat Example

-

Kick Drum Example

-

Snare Drum Example

-

Tom Tom Example

These are some Drum examples. While all the drums are different and Subtractor is capable of producing a wide variety of drum sounds, there are some common characteristics. For example, most drum sounds don’t have any Sustain, and also have extremely short Attack — usually set to zero. There is minimal Decay and Release as well. So set up the Amp envelope with this in mind. In addition, your drums may or may not require pitching up or down, so you can disable the keyboard tracking for the Oscillators. Then use the Oscillator tuning to get them to sound accurate (usually in the lower register). This way, the drum will sound at the same pitch no matter where you play it on the keyboard. However, this may or may not be what you want.

Filtering is also important for drums. Generally, Bass, Snare, and Tom drums use Low Pass filtering. While Hi Hats, Crashes, Cymbals, and the like use Hi Pass filtering. The Noise generator can be very helpful here as well. For low Bass Drums, be sure to turn the Color knob closer or all the way left. This brings the register of the noise downward. For more of a biting drum, like a Snare, turn the Color knob closer or all the way to the right.

-

Mod Pad Example

Here’s an example of a Pad – a String Pad actually, which use two Sawtooth Oscillators (great for achieving nice string pad sounds). The idea behind creating a nice Pad sound, in my opinion, lies in two areas: A) The Amp Envelope settings, which are fairly slow. This means that the Attack, Decay, Sustain, and Release are generally pushed up quite high (over a value of 60 in most cases). And B) The modulations you create, which are usually slow as well. This can be anything from the LFO affecting the Mix or Amp, while the Mod Envelope affects the Phase of the Oscillators. The Rates for the LFOs should be set fairly slow (Rate knob more to the left) and the amount values should be subtle (more to the left) as well. This creates very soothing and meandering sounds which work well for Pads.

Of course, never forget that rules are meant to be broken, and nothing here is set in stone. I’m just presenting you with some generalities.

-

Morse Code Example

-

Noise Doppler Example

-

UFO Effect Example

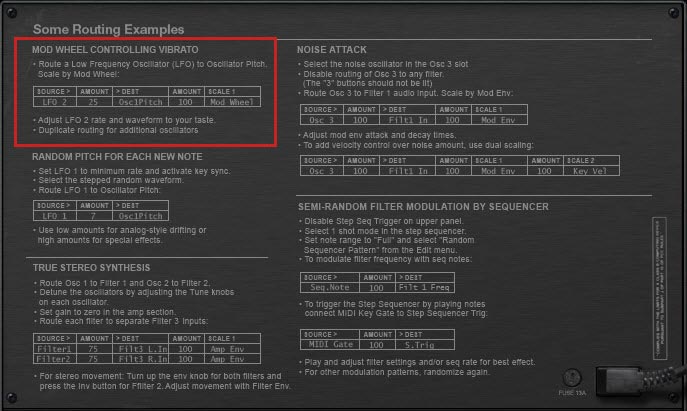

These three show how you can create various special effects with the Subtractor. The Morse Code patch is a good example of how you can use the Random LFO 1 applied to the Filter Frequency in order to create a random Morse Code Sonar sound. Depending what Oscillator you are using and how it’s filtered, you can have it sound like a Telegraph, if you like. So give that a try.

The Noise Doppler Effect is a good example of how you can use the Noise generator on its own, without any Oscillators. The noise is modulated with the two LFOs to create a pseudo-doppler effect. Then the Mod Envelope is used to control Frequency Cutoff on the Low Pass Filter 2. And the Filter Envelope is affecting Filter 1. This all creates a double filter sweep that brings the sound in slowly as it’s sustained. Try playing a chord and note how the sound gets louder over time (as the filters are opened). The LFO 2 plays its part as well by cycling the Amp. A lot of mods working in tandem to affect a very simple Noise generator. Fun stuff!

And finally there is the UFO effect which showcases how you can create some interesting Alien-type sci-fi sounds. As with all the patches here — but moreso in this particular patch, try using the Mod Wheel to show some variation in the sound.

-

Organ Example 01

-

Organ Example 02

-

Piano Example 01

-

Piano Example 02

These four patches are examples of how to recreate organ and piano sounds using the Subtractor. I don’t know about you, but I find programming Pads, Pianos, Organs, and Basses are probably among the easiest types of instruments to reproduce with the Subtractor. I’m not going to go into all the details of how these patches are put together, because they all use different settings, Oscillators, Filters, etc. And you can take a look at them for yourself and then try your hand at creating similar kinds of sounds. I would say that a good starting point is a Sine wave and Low Pass filter though. Sometimes a Notch filter can work well. It all depends. So here are four examples.

-

PWM Lead Example

This shows how the Phase is used to offset and modulate the Oscillator wave, creating “Pulse Width Modulation” (or PWM for short). This is also referred to as “Phase Offset Modulation” (POM). Essentially, its the same thing.

-

Rhythmic Example

In this patch I tried to show how you can get some very complex rhythms using the two LFOs and the Mod Envelope together. The Mod envelope is applied to the pitch to create a sound that continually moves downward. LFO 1 is applied to the Filter 1 Frequency Cutoff to create a gate-like rhythm to the sound. And LFO 2 is applied to the Phase to create a PWM as Phase is swept back and forth. 2 things you can do: A) Try reversing the direction of the sound by inverting the Mod Envelope (click the upside down ADSR graphic button at the top right of the Mod Envelope section). B) Try adjusting the Rates of the LFOs. You can sync them to each other by keeping their rate values identical. You can separate their sync by using two different rates. It’s up to you. But this is different than syncing the LFOs to the tempo of the song; something else you can try out.

Tips for working with the Subtractor

Aside from the basic Oscillators, there are several other wave samples that are hard-coded into the device (represented by waves 5 through 32 in the Oscillator slots). Then there are the usual things that are familiar to most analog synths: 2 filters, 3 envelopes (Amp, Filter, and Mod), 2 LFOs, Noise generator, FM and Ring Modulation, Pitch Bend & Mod Wheels, and a very extensive Velocity parameter section. All of this should be familiar to the synthesist and sound designer, and I’m not going into all the ins and outs here. The Reason User Guide is an excellent resource which goes over most everything you will need to know in order to get familiar with the Subtractor.

What I do want to cover here are a few pointers that may not be obvious when using the Subtractor, or might cause some confusion when you begin to work with it. Think of this as some additional insight into the device which sooner or later you would figure out on your own. Maybe this might save you the trouble?

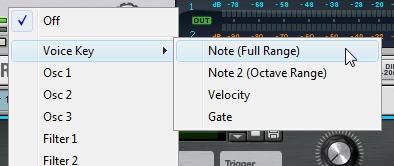

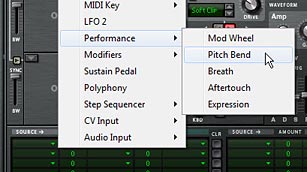

- The Subtractor is monaural in two senses: It creates a single channel of sound, and can only generate one sound at one time. However, the device is polyphonic, in that you can play that same sound using multiple keys (think: chords). The number of keys that can be played at the same time is set up in the Polyphony setting (1-99). However, what you may not know is that some of the modulation is polyphonic as well. I know this sounds a little counter-intuitive, but here’s the deal: If you set up your patch to have a Polyphony setting above 2 (usually you want this higher at 8 or 12), then you can use LFO2 to affect the Oscillator 1 & 2 Pitch, Phase, Filter 2 Frequency Cutoff, or Amp. If you do this, playing a broken chord (one note after another) results in an LFO that retriggers separately for each note. This is different than the LFO 1 in the Subtractor, which is a global or monophonic LFO, meaning it does not retrigger with each new note.

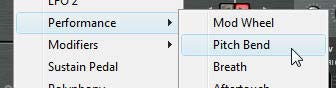

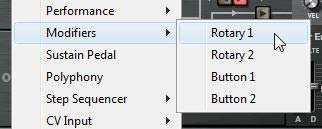

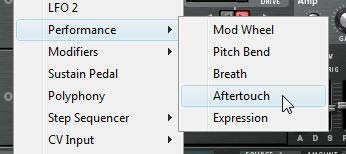

- Using the LFO 2 to affect the Amp is the way in which you set up Tremolo. It’s a shame that you can’t apply this Tremolo to the Mod Wheel inside a Subtractor patch (a fairly common Mod Wheel assignment), however, you can do this if you put the Subtractor inside a Combinator, and assign the Subtractor’s LFO 2 Amount to the Combinator’s Mod Wheel.

- Those who are new to the Subtractor may not know that in order for FM or Ring Mod to function, you need to have both Oscillators enabled. This is because both of these features rely on the interaction between the two Oscillators. In addition, if you want to hear only the Frequency Modulated sound, without the Modulator, turn the Mix knob fully left. If you want to hear the Ring Mod sound without the Modulator, turn the Mix knob fully right.

- The Noise generator is also similarly connected to the second Oscillator output, which means turning the Mix knob fully left while the Noise generator is on will reveal nothing from the Noise generator. To hear the Noise generator fully, turn the Mix knob fully right. Therefore, to get a mix between the Noise generator and an Oscillator, turn off Oscillator 2. Instead, set up Oscillator 1, turn on the Noise generator, and keep the Mix knob centered. If you instead want a pure noise sound, keep Oscillator 2 turned off, and turn the Mix knob fully right. This removes Oscillator 1 from the Mix and fully introduces the Noise generator.

- And as with all rules of thumb, there are always exceptions. If you disable Oscillator 2 and enable the Noise generator, you can still use the FM knob to modulate Oscillator 1 with the Noise generator (remember that the Noise generator outputs where Oscillator 2 is output). You are effectively using the Noise generator as the second Oscillator, and this is used as the Modulator to Frequency Modulate Oscillator 1. So yes, there are exceptions. And while all of this may sound complicated, it’s really not. Think about it. Turn on Noise, increase FM, and turn the Mix knob all the way left. Then experiment with the various Oscillator 1 and Noise generator settings to see what you can come up with.

- If your Oscillators are set to “o” as opposed to “-” and “x,” then the Phase knobs have no effect on the sound. Phase only works with subtractive (-) and multiplied (x) modes. You can, of course, set up mode combinations where Oscillator 1 is set to subtracive (-) and Oscillator 2 is set to “0.” In this case, only the Oscillator 1 Phase knob will have any impact on the sound.

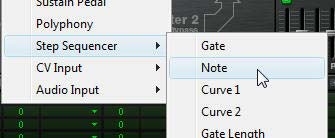

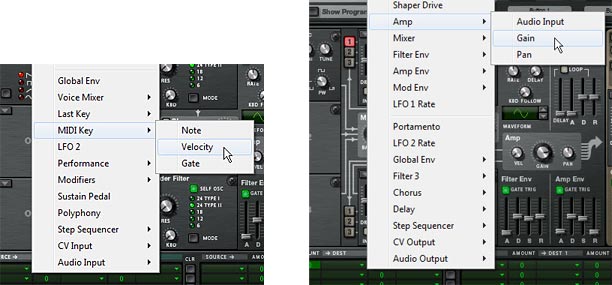

- The Velocity section can have an amazing impact on how the sound is played, and has a wide array of options. However, where a lot of new users get confused is in how to set up the Velocity knobs. First things first. Set up a matrix or Thor Step sequencer to play a single note repeatedly at a relatively slow speed, and create a velocity ramp up and down over the duration of the sequence (ramp the full range of the velocity). This sets up the sound to be played at the same pitch, with only the velocity changing as the notes are played. It also helps you to hear what’s going on with velocity. With that done, start experimenting with the 9 velocity knobs to hear how they interact and affect your sound.

- Another thing to keep in mind when adjusting velocity parameters: When the knobs are dead center, velocity has no effect on the parameters. Turn the knob to the left and velocity has a negative impact on the parameter in question. Turn the knob to the right and the velocity has a positive impact on the parameter in question. In simple terms, if you adjust the Amp velocity in a positive way, the sound becomes louder the harder you play your keyboard (normally what you would expect). However, you can reverse this relationship by adjusting the amp velocity knob in a negative way, so that the sound becomes quieter the harder you play your keyboard.

- And more about the velocity parameters: Note that if you have a parameter that is adjusted fully one way (for example, the Filter 1 Frequency slider is set to 127 or fully open), then adjust velocity to increase this parameter in the same direction (for example, the Filter Frequency velocity knob is adjusted in a positive direction), the velocity will have no impact on the sound. This is because the Filter Frequency is fully open, and can’t go any further. You could, however, adjust the Filter Frequency in a negative direction in this example, in order to close the filter the harder you play your keyboard.

- Finally, one last note about the Phase Velocity parameter. Adjusting this will adjust both Oscillator Phase knobs in tandem by the same proportion. This means if you have one Phase knob set to 40 and another Phase knob set to 80, with the Phase Velocity knob set to 10 (positive), when you play the keyboard at full velocity, the Phase knobs will sound as if they are set to 50 and 90, respectively. You can, of course, set up one of the Oscillators to a mode of “o” as outlined earlier, so that the Phase of that Oscillator has no effect on the sound. Of course, this can change the sound. This tandem shifting of Phase is also true of the Phase knob that can be used as a destination for the Mod Wheel. So bear this in mind when adjusting these two parameters.

- In case you were ever wondering, that second filter in Subtractor is a 12 dB Low Pass Filter, and it cannot be changed to any other Filter Type. Also, when working with it, turning it on will mean that the sound passes through Filter 1 and then into Filter 2 (Serially). With this setting, you can use the Frequency Cutoff sliders of both filters independently (and in some interesting ways — for example, setting up a High Pass Filter 1 and then having it go through the Low Pass Filter 2). Alternately, you can “Link” the Filters together. When they are linked, the Frequency Cutoff of Filter 1 controls the Cutoff of both filters (but the relative position of Filter 2’s Cutoff Slider is maintained). For example, if Filter 2 is set to 50, and Filter 1 is set to 80, moving the Filter 1 Cutoff Slider down to 70 will also reduce the Filter 2 Cutoff to 40. They work in tandem. Note: Low Cutoff Frequencies with High Resonance settings can produce severely loud sounds. This is amplified by the “Link” feature. As such, it’s always a good idea to A) Turn down the Resonance for both filters to zero before applying the “Link” button. And B) Turn down the volume if you are experimenting with the Resonance of either filter while the “Link” button is activated.

- Filter 2 does have its own dedicated Filter Envelope. Use the Mod Envelope with a destination of “Freq 2.” Now you can control Filter 1 Frequency Cutoff with the Filter Envelope and Filter 2 Frequency Cutoff with the Mod Envelope, all at the same time. This allows you to create some pretty complex filtering in your patches.

- Lo BW. Unless you are rockin’ out with your PII Pentium 200 Mhz computer from 1994, you will never need to enable this feature. Just pretend it’s not there.

- Want a fatter sound? If both Oscillators are set to the exact same settings, detune them by a few centos in opposing directions (Oscillator 1 = -4 Cents / Oscillator 2 = +4 Cents). You’ll have to venture outside a simple Subtractor for other fattness tricks, but two of my favorites are A) creating a Unison device under the Subtractor (between the Subtractor and the Mix Channel). This automatically fattens your sound. B) After you have the Subtractor patch set up exactly as you want, duplicate the Subtractor and send both subtractors to separate Mix Channels. Then on the Mixer, pan Subtractor 1 fully left and Subtractor 2 fully right.

So that’s a little bit about the basics of the Subtractor synth, along with a new patch pack. I hope you’ve enjoyed it, and if you have any tips or ideas related to using the Subtractor, please share them. All my best, and happy sound designing!